I’ve completed dozens of bond surrender cases this year, and encountered several recurring themes and common pitfalls when dealing with bond surrender calculations. These calculations can be fiddly, especially if you haven’t dealt with one for a while. Dealing with changing regulation on certain aspects (I’m looking at you, top slicing relief) can make it easy to overlook or forget certain aspects. I hope this blog is a helpful memory jog on the more finicky aspects of bond surrenders.

Unintended Consequences

- Student loan repayments: Remember that bond gains are taxable income, so even if there’s no tax due on the gain, a bond surrender could lead to the recipient having to repay more of their student loan. Depending on their circumstances, this might be taken from their salary via PAYE.

- Tapered personal allowances: Similar to the above point, there might be no tax to pay on a gain, but the gain might increase the client’s annual income to a level that they lose an element of their personal allowance.

- Care costs: As long as the investment isn’t treated as a deliberate deprivation of assets, bonds are often ignored by a Local Authority when a client is being means-tested for care funding. This is something to be aware of if an older client who has held a bond for a long time is considering surrendering it and holding it as cash, for example.

Bonds in Trusts

Normally, a bond gain falls on the policyholder and becomes part of their income for tax purposes. This is similar for absolute trusts, where the gain falls on the beneficiary.

For bonds held in other types of trust, the rules are a little different:

- If the settlor is a UK resident and alive in the tax year of the gain, the gain falls on them. The settlor can reclaim any tax they pay from the trustees.

- If this isn’t true of the settlor, the gain falls on any UK resident trustees. Note that the old £1,000 standard rate band has been removed, so all gains that fall on the trustees are taxed at the trustee rate of 45%. If the trust only receives income below the allowable tax-free amount (usually £500), then the trust doesn’t have to pay income tax. If the trust receives more income than the tax-free amount, tax is due on the whole amount of income.

- If there are no UK resident trustees, the gain falls on the UK beneficiaries.

The Timing of Bond Gains

This is a small but easily overlooked point: the two types of bond gains are taxed at different times.

Surrendering whole segments will result in taxpayers having to pay any tax on the gain in the tax year the surrender was made.

On the other hand, if you make a withdrawal across all segments, the tax on the gain will be payable in the tax year that the policy year ends in. For example, take a withdrawal made via this method on 1st April 2024, where the policy year ends on 1st September 2025. The withdrawal takes places in the 2023/24 tax year, but the gain will be taxed in the tax year that 1st September 2025 falls into, i.e. the 2024/25 tax year.

Order of Tax

Onshore and offshore bond gains are savings income, and they can both potentially make use of the Personal Savings Allowance and Starting Rate for Savings. However, they’re not treated identically for tax purposes.

Onshore bonds are treated as the top part of income, and are taxed last, after non-savings income, other savings income and dividends. Offshore bonds slot in with other savings income, so are taxed before dividends and after non-savings income.

Top Slicing

Interaction with Personal Allowance, Personal Savings Allowance and Starting Rate for Savings

There have been some recent changes to these rules which can catch you out if you don’t deal with bond surrenders regularly.

In mid-2023, HMRC updated their guidance on how the above three allowances interact with top slicing relief. Prior to this updated guidance, when calculating the tax due on the average gain for top slicing purposes (step 4 of the calculation), you used the client’s income plus the full gain to determine whether the PSA and SRFS were available. On the other hand, eligibility for the Personal Allowance was based on the sliced gain, so you could potentially reinstate the Personal Allowance.

After the updated guidance, for step 4 of the calculation, the amount of PSA, SRFS and PA the client is eligible for is based on the sliced gain, not the full gain.

It’s important to note that this is only applicable to step 4 of the calculation, and not the calculation as a whole. Nevertheless, this could still result in some clients paying less tax.

Eligibility

Only individuals can claim top slicing relief. As bonds in absolute trusts are typically taxed, as though the beneficiary owns the bond, beneficiaries of absolute trusts can also claim top slicing relief.

For other types of trusts, if the trust assigns segments to a beneficiary, that beneficiary can claim top slicing relief going back to when the bond was established. Trustees cannot claim top slicing relief. Settlors can claim top slicing relief.

Top Slicing Years

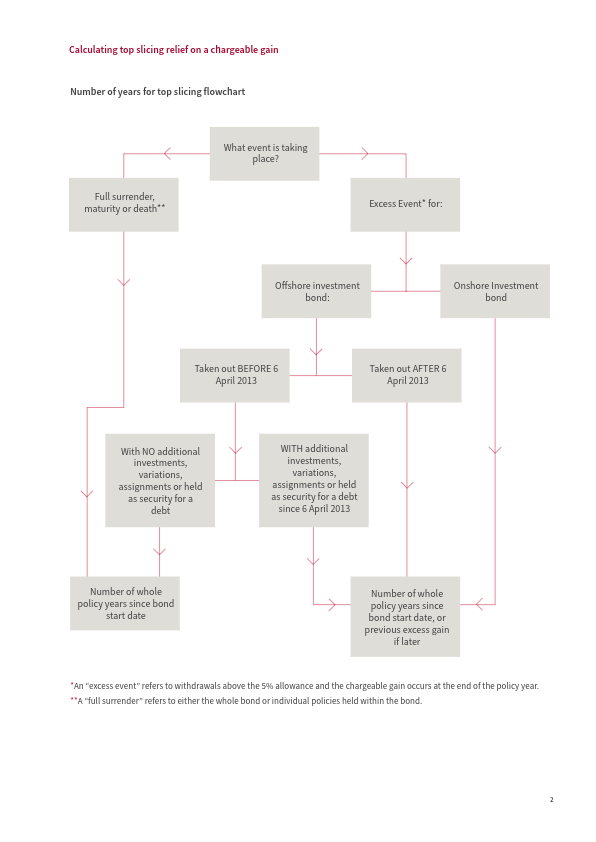

Working out how many full years to use in a top slicing calculation can be tricky, as it depends on whether the bond is onshore or offshore, the type of surrender, and when the bond was established.

If you’re surrendering the whole bond, or whole segments, you can use the number of full years since the bond was established.

If the gain has been caused by an excess event (taking a withdrawal above the 5% allowance from across all segments) and the bond is onshore, you use the number of full years since the last excess event. In this situation, but with an offshore bond, it gets a bit more complicated. Luckily, there are some handy flowcharts available online. I have used the one below from Canada Life as an example.

This is just a quick roundup of some of the things to look out for when doing a bond surrender calculation. Are there any other tricky areas that might catch you out when doing a bond surrender?